I recently read Kit Holden’s Played in Germany. A book I purchased during last summer’s Euros (but only just got round to reading) detailing the history the beautiful game in Germany.

As the subtitle, A Footballing Journey Through a Nation's Soul, suggests, it’s more than just an account of some of Germany current and former biggest clubs. Rather, football is used as a means of explaining the country’s identity and some of its problems. Holden takes us on a journey through the land, weaving in fascinating accounts of its clubs, their fans, and what both can reveal about the country’s tumultuous history. The reader will learn much about the issues facing German clubs today and how these are a reflection of matters faced by contemporary German society.

As with so many aspects of modern German life, history weighs more heavily on their football clubs, and the mentality of their fans, than is the case in most countries.

Germany and football are synonymous. From the passion of their fans to the historic achievements of their national team. With 4 World Cups and 3 Euros under their belt, only Brazil and Argentina can boast more major international trophies. The stereotype of Germany as a footballing nation is one the country is happy to embrace (particularly given many of the more negative stereotypes which are only recently beginning to fade).

It is certainly a stereotype held by many in England, sometimes tinged with a bitterness at the country’s historic successes compared to our own history of disappointments (a mirror for our two countries economic performances over a similar period).

I’ve written at length about the British habit of using Germany as a benchmark to measure our own successes and failures. In few other fields is this benchmarking more apparent than football.

It is a strange twist of fate that the recent successes of the English men’s team in the last 8 years has coincided perfectly with German failures. Admittedly England have yet to win a major title, but a run under Gareth Southgate of two Euros finals, and a semi-final and quarter- final in successive World Cups is still the best the English team have had in its history. During the same time Germany underperformed in all four of those tournaments. Failing to even get out of the group stage in the last two World Cups and losing to England in the last 16 in Euro 2020 – the first and only time England have beaten Germany in the knockout stages of the tournament aside from 1966.

Yet even during Germany’s lowest ebb as a footballing national, they were still held up as the gold standard. Southgate, in an interview a few years ago, stated: ‘we’ve learned an enormous amount from studying Germany… they’ve had a big bearing on what we’re doing… We studied Germany at the 2014 World Cup and their development of their youth teams… they modify their system and are constantly evolving…’ There is always the feeling that the German national team may be down, but never out. This is but a temporary blip from which they will rise back to the top. That is the natural order of things.

Respect for German football is not limited to the national team. In the past decade, British interest in German club football has also grown. Since the late 2010s games from the Bundesliga (Germany’s top league) started being aired on British subscription channels like ESPN and BT Sport, allowing British viewers a chance to watch German club football on a regular basis.

This interest skyrocketed during Covid 19. Another area of life in which Germany seemed to be so much more successful than Britain was in its handling of the pandemic. Historical analysis will be the judge of that, but at the time it did mean the Bundesliga resumed far sooner than football in Britain. BT Sport reported a 400% increase in viewership in Britain of Bundesliga games compared to pre-pandemic averages. Websites ran stories helping British fan decide which German clubs to support.

Interest in, and respect for, German club football grew further during the European Super League debacle in 2021. When many of European biggest clubs (read wealthiest, not necessarily best performing) tried to form a breakaway league, US style with no relegation, outrage among fans was understandably off the scale.

Notably absent from the league’s proposed founding members were any German clubs. Even Bayern Munich, arguably one of Europe’s biggest clubs and footballing brands, had the foresight and sense to avoid the plans.

This brought an aspect of German domestic football to British attention most had never heard of – the so called 50+1 rule. This is a clause in the top two leagues of German football that require clubs to be majority owned by the club itself, usually through membership associations (i.e. fan groups) rather than outside investors.

Yet, as with all the ways in which Britain benchmark Germany, football is not as rosy as we like to think. A topic upon which Kit Holden’s books sheds a lot of light.

Holden starts his book in Leipzig in an attempt to show how the division between the former east and west in Germany is very much reflected in its football clubs. These cultural divisions are something I have often written about, having lived in the former east myself.

Those in Britain with a vague knowledge of German geography may be aware that Leipzig lies in the former east. They will more likely be aware that it is home to one of Germany’s top clubs – RB Leipzig.

Supporters of the club like to portray it as one of the few East German footballing success stories. Yet this isn’t really the whole picture as Holden illustrates.

The club’s official full name, RasenBallsport Leipzig, is something of a play on words because most people know them as Red Bull Leipzig. The energy drink brand’s logo form part of the club’s crest, the team play at the Red Bull Arena and are known as die Roten Bullen in German. Though the club’s membership associations still have majority formal voting rights to ‘officially’ adhere to the 50+1 rules, Red Bull effectively has complete ownership and calls the shots.

The club wasn’t even founded until 2009. Nearly 20 years after reunification and has very little claim to be considered an ‘eastern’ success story.

Look around the former east and there are very few clubs anywhere near the upper echelons of German football. And this is a result of how football was managed post reunification.

The GDR had its own footballing pyramid with the Oberliga at the top. For all the differences between the two German states, a passion for football was something they certainly shared.

After reunification the East German clubs were integrated into the West German Bundesliga, with only two clubs, Hansa Rostock and Dynamo Dresden being permitted into the top tier. Along with virtually all East German clubs these have struggled since. As with most aspects of reunification, no attempt was made to create something unified; anything from the east was simply forcibly merged into its western counterpart. Reflective of western attitudes and the root of resentments that still simmer. Football certainly fell under this trend.

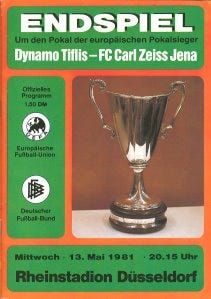

When I lived in the former east, none of the kids at the school where I worked supported former eastern clubs (though a flatmate did have a Hansa Rostock flag in our shared kitchen). The biggest such club nearby was probably Carl Zeiss Jena. They had been a giant in the former Oberliga and their successes were not limited to the domestic front, having reached the European Cup Winners’ Cup Final in 1981. Since reunification they have struggled to compete financially with the wealthier western clubs and remain minnows in the lower German leagues.

1981 European Cup Winners’ Cup Final Programme

Though Union Berlin are cited as one of the recent success stories, Berlin’s complex position within East-West relations is a more complex matter and subject of a longer post.

The East-West divide is only one aspect address by Holden in his account, albeit the one that resonates most with me. We also learn about corporate sponsorship.

Another positive stereotype many in England have about German football is that its clubs are less beholden to corporate sponsors.

Clubs like VfL Wolfsburg show this is not always the case. Fully owned by Volkswagen AG, it probably has the closest relationship of club and corporate anywhere in Europe, the club being fully exempt for the 50+1 rule. There were major concerns over how VW’s emissions scandal in 2015 would impact the club, though they seem to have weathered the storm.

Nor have big German clubs been able to fully resist sponsorship money from companies in countries with questionable human rights records as Bayern Munich’s deals with Qatar Airways or Hamburg’s with Emirates prove. Though it should be acknowledged that no major club is currently sponsored by companies from Saudi or the Gulf.

Then there is FC Schalke 04. Long sponsored by Russian oil giant Gazprom until the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 made the deal too awkward. Also a reflection of the country’s wider reliance on cheap Russian gas and its willingness to turn a blind eye to latent dangers in that over-reliance.

Gazprom logos hastily covered. Photo from Spiegel Online

Perhaps most depressing is the notes on which the book ends – as money and corporate power (not to mention shady billionaires and petrostate dictatorships) come to dominate European football, how long can Germany hold its own? So far Bayern Munich have done a fairly good job of balancing being a local club and an international giant. Holden highlights the club’s history of support for Jews in the face of Nazi opposition as well as continued involvement in local events. But can this balance last if Bayern wish to continue going tot to toe with clubs like PSG or Real Madrid?

Football is one of the many things that ties Britain and Germany together. Something I have written about with appointment of Thomas Tuchel last year. His results haven’t inspired too much hope so far but next summer at the World Cup will be an interesting time.

As Kit Holden demonstrates, we can still learn a lot of positive things from the German footballing system and the fiercely local support of their fans. But as with everything, the grass is always grüner!

I’d like to give a shout out to

whose Substack on German football is outstanding and also ’s Sports & Geopolitics– thoroughly recommend giving them both a follow.

Thank you so much, Matthew! Really kind of you. Much appreciated.

when I see criticism of the power of money in football with the Bundesliga held up as an attractive exception where supporters still count for something, they conveniently forget that it is also the least competitive of the major European leagues