This week I finally finished Freedom, Angela Merkel’s memoirs. At 700+ pages, it’s fair to say it has been a slog. My own personal Everest.

Anyone who has already read a biography of Merkel will find little new to be discovered in her own account. But, as with all political memoirs, there is as much to be learnt from what is not said, as what is. The popularity of the publication in the UK can also reveal a lot.

Kati Morton’s The Chancellor (2022) or Matthew Qvortrup’s Angela Merkel: Europe's Most Influential Leader (2021) both provide detailed and insightful overviews. Yet neither has been as popular nor talked about in Britain as Merkel’s own account.

It’s hard to imagine the memoirs of any other contemporary European head of state, even a British one, being as eagerly anticipated in the UK as those of Angela Merkel. I can’t remember other political biographies featuring so prominently in bookstores across the country in recent years. Not even those of our very own Liz ‘the cabbage’ Truss.

I ordered the book from Waterstones when it was released at the end of last year. Rather embarrassingly I opted to pay extra for a signed copy, which after a few weeks of waiting, I was told they no longer stocked. I don’t know whether that was a website error and Merkel had in fact never signed randoms copies for a British retailer, or if it was so popular it simply flew out the warehouses in minutes. At any rate, one of my children spilt a glass of water over the version I eventually bought, so probably best it wasn’t a ‘collector’s item’!

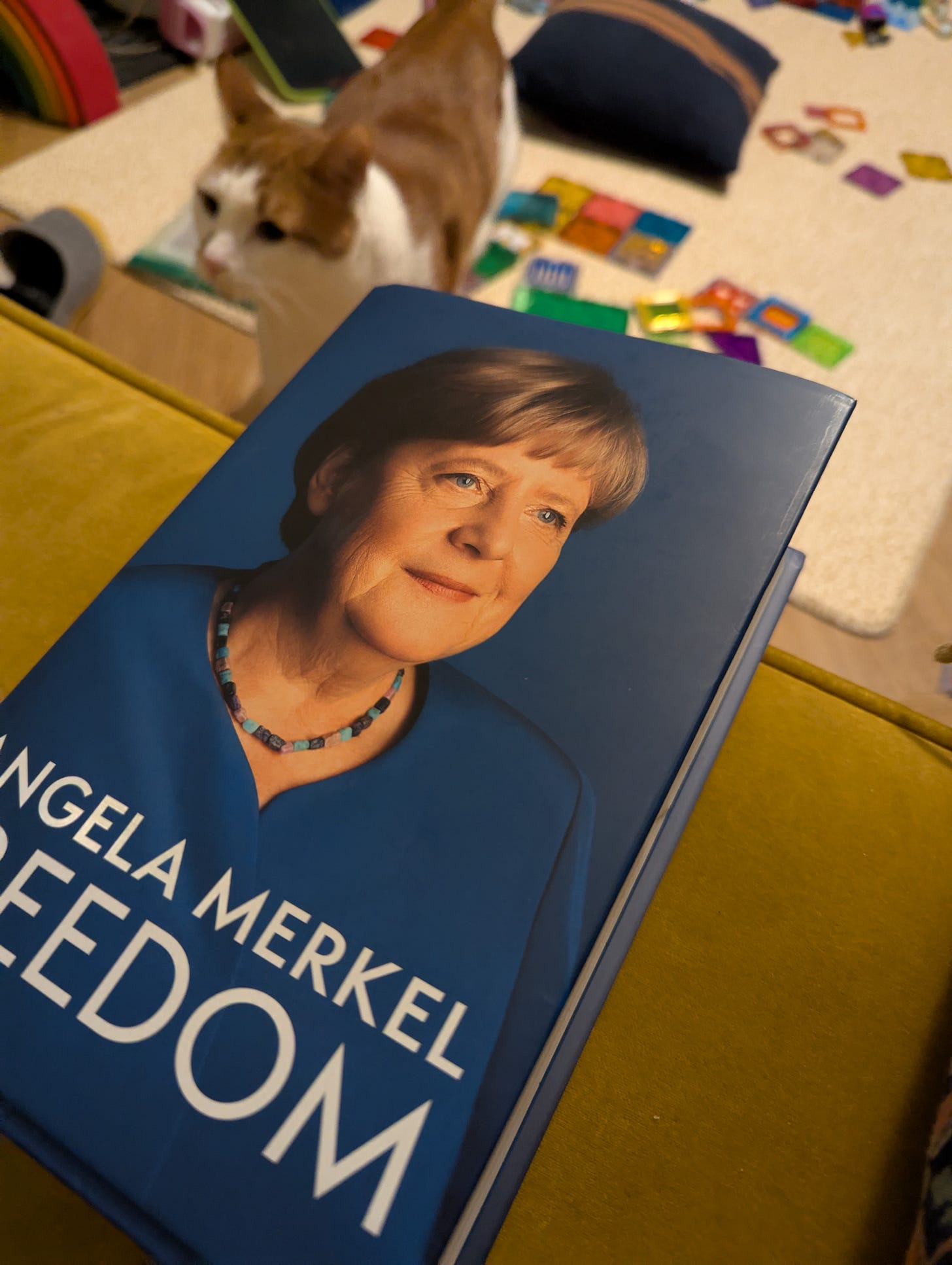

Your author, shortly after purchasing

When I purchased my copy from a local book shop (Backstory in Balham thoroughly recommend) the man behind the till told me it had been one of their most popular items sold over the Christmas period. I’m aware this was a liberal, well-heeled part of southwest London, and not necessarily a reflection of the political views or reading habits of the wider nation, but still.

Popular with all members of my household

Part of the popularity is of course down to the duration of her tenure as Germany’s second longest serving chancellor at 16 years. She has been a constant on the European and world stage for most of the major events this millennium and for people of my age or younger, has been a formative part of our views on Germany itself. Indeed, it has been difficult to imagine the country not led by her.

Yet it also speaks to the enduring fascination that many in Britain have with Germany. Something the sheer volume of books about the country can testify (see my last post on two of these).

The memoirs themselves are often dry. Lots of detail of summit names, conferences attended, and laws passed (I didn’t even attempt to read it in the original German). One of the things that first struck me is how little is really revealed about her personal life, or feelings. For a country famed for inward-looking, self-reflective literature, any such romanticism is lacking here.

She mentions meeting, marrying, and divorcing her first husband, Ulrich Merkel, with such little detail one is left asking a lot of questions. Similarly with her current husband. He is referred to as someone on occasional holidays or events, but with virtually no personal detail. Perhaps this is just the natural manner of someone who likes to keep her private life private, but one would expect a little more detail in a book about her life, as opposed to just her time in office.

Though lacking in the personal, one thing that did strike me was her obvious passion for and knowledge of classical music. Something that is typically German. Such constant references to attending operas or concerts would sound contrived from most British leaders, excepting perhaps Ted Heath. But it is genuine in Merkel.

On the political front, I often found myself feeling disappointed on the lack of detail, especially concerning her first steps into politics and meteoric rise within the CDU or personal details of those she knew. Anyone hoping to read any salacious gossip or scathing opinions of the various political leaders she has worked with will not find that here.

Again, perhaps this is understandable. That is not Merkel’s character. She is humble, respectful, and private. Traits that make her admirable as a person and a politician. She is also self-aware. Merkel may have left office, but one never leaves politics. Her opinions still matter and carry weigh. She is painfully diplomatic in her writing. Her views on Trump as close as we get to revealing the irritation she must have felt and disgust with him as an individual –‘I had acted as though I was having a conversation with someone normal’.

We get the occasional insights into the struggles she faced in being a woman, from the east, and the discrimination she faced as a result. But not much around how it made her feel, and, for me at least, not enough about how this was reflected in wider society after reunification.

Much of the work is spent justifying her political decisions. That is not a criticism. One would expect as much from any political memoir. Regarding her most controversial decisions, which weigh ever heavier on Germany today, and increasingly sully many people’s opinions of her, she devotes many words.

The global financial meltdown in 2008 and subsequent Eurozone crises get a lot of space and are one of the areas of the book I did find fascinating (if you’re into that sort of thing). Her administration’s decision to install the debt brake in 2009 (severely, and many argue unnecessarily, limiting the country’s structural deficit limits) is one she stands by despite the economic pressure it later caused. This has since been removed as I discussed in a previous post.

Her decision to close German nuclear power plants after the Fukushima disaster in Japan in 2011 is covered. Nuclear energy has always been a sore spot in German history, in a manner that has never been the case in Britain or France or elsewhere. Probably a topic for another post, but in itself, never that surprising. The decision did though mean ever more reliance on cheap Russian gas, even if renewables usage did increase as well.

Indeed, her relationship with Russia is something readers in Britain, the US or elsewhere may find surprising, especially having grown up under a Russian puppet dictatorship. While she is always critical of Soviet oppression and clearly found Putin distasteful and difficult, she has a fondness for Russia itself. Speaking the language fluently and having travelled there in her youth. Again, this is not a criticism and perhaps reveals a better understanding of the country than many other western leaders have. Especially recognising the fact that Russia will not go away and must be worked with, rather than against, however distasteful this may be. This both epitomises Merkel’s own approach to compromise and discussion above all else, but also the centrality of Russia and Russian influence on German history, which those in other states often fail to understand. This feels particularly galling when she attempts to justify her decisions to prevent Ukrainian and Georgian accession talks into NATO back in 2008. Given subsequent events one could see this as an error, Merkel claims it would have been worse. A cynical way of viewing matters would be the German tendency to avoid hard decisions, kicking the can down the road, then blaming outcomes on things out of their control.

It is the 2015 migration crisis, which gets some of the most coverage. She recognises the impact of the decisions she made at this time in terms of opening the borders, going as far as to see September 2015 as a turning point in opinion of her. Despite some of the consequences of these decisions one is struck by how genuine her compassion and commitment to treating humans with dignity is. Not political grandstanding. Indeed, this is probably the topic in which she goes furthest in rebuking CDU colleagues and German mainstream parties in general, for pandering to populism and imitating the policies of the far-right AfD.

For a British reader, it is what is not said that will prove most striking. Britain is rarely discussed at all. Occasional meetings with British PMs are listed, rather than discussed, with zero insight into her views on the people or the country (I was really hoping for some comments on Boris!) It is always the EU, the US, France, and Russia (usually in that order) at the front of her mind.

Brexit is barely covered. When one thinks of the significance and centrality of Germany to the Brexit debate, by both the Leave and Remain sides, this will come as a big shock to British readers. For those in the Leave camp German migration policy was central in arguments to gain control of our own borders, as was Germany in general and Merkel in particular, seen as crucial in guaranteeing future trade deals. For liberal Remainers, Germany and Merkel were seen as the pinnacle of all Britain should aspire to be, our City on the Hill.

For Merkel, 3 and half pages are given. Barely even a sub-header within another chapters. She describes her feelings at the time of the result in June 2016 as a ‘humiliation… a disgrace for us’ [my italics – indication that she always thinks in EU terms] and then nothing. No detail around the protracted negotiations and the shitshow that unfolded, indeed is still unfolding, in the UK.

I found myself wondering how far this absence of discussion around Brexit, or Britain more generally, was a result of wounded pride, sadness, and a determination to write the UK out of the European story. Understandable emotions, though Merkel rarely displays strong emotions elsewhere and is always guided by practicality. Or is it that the UK simply isn’t as important to Germany as we like to imagine? Possibly a little of column A, but likely more of column B.

I’m a fan of Merkel. I respected and admired her throughout her tenure as Chancellor as did so many in Britain, and around the world. Though her reputation has suffered in recent years due to a number of her decisions, she still represents the embodiment of calm, sensible politics in an age of growing populism. Consensus, human dignity, and peace in a world where all seem to be disappearing rapidly. She remains more popular in Britain than her homeland.

For all her faults and the dryness of this book, it shall still retain a prominent place on my bookshelves, as she always will in my opinion of the world leaders in my lifetime.

Love the photo😊